- Home

- Peter Doherty

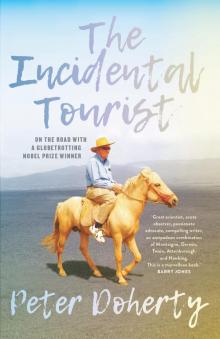

The Incidental Tourist Page 10

The Incidental Tourist Read online

Page 10

Carrion eaters may not be universally loved but they are key players in nature’s sanitation system. When India’s ‘sacred cattle’ die, tradition demands that they remain where they fall to be stripped bare by vultures. That worked fine until veterinarians started to use the human non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSA) Diclofenac in animal husbandry. Though harmless in us, even trace amounts of this NSA in cadaveric soft tissues are incredibly toxic for the vulture kidney. The consequence is death from visceral gout, caused by the accumulation of white uric acid crystals (the normal excretory product of birds) throughout the body. Eliminating the vultures has also impacted directly on human health, with an increase in fatal rabies cases as wild dog populations have expanded to fill the scavenger void.

Moving back and forth from the Windsor over the next few days, the vulture deficit wasn’t the only reality that reminded us how the world has changed for the worse. As a complex, democratic society, India works remarkably well, but the 2008 Taj Mahal Palace Hotel attack in Mumbai dispelled any illusion of immunity from terrorism. Approaching the Windsor, the limousine was held at barrier gates till armed guards had checked thoroughly for explosives. Allowed to drive on, we then entered the hotel lobby via a metal detector. The possibility of random violence also determined the secure siting of the hotel restaurant. The days of dining while separated only by glass from an active streetscape are long gone for many major city hotels.

This was our first visit to Bangalore, which I’d long thought of as higher, cooler, smaller and cleaner than, for instance, Mumbai and New Delhi. The city is 900 metres above sea level, though, with a population of more than eight million, the traffic is only marginally less awful than the vehicular chaos of Delhi. But the air seemed better and Bangalore has beautiful, well-maintained and very extensive public botanic gardens. Even so, it was (with the vulture story in mind) a bit disconcerting to see young families sharing the open space with large numbers of wild dogs. The kids were probably safe, though, as India has an aggressive program of canine sterilisation and rabies vaccination.

Along with the situation for other fast-growing cities across the planet, Bangalore is facing serious environmental stresses. A local journalist made the point that the water supply, which is largely from pumped aquifers, cannot be expected to cope with the continued construction of new apartment blocks. Indeed, the exhaustion and contamination (arsenic accumulation) of ground water is an inexorable progression throughout India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, which has the added difficulty of saltation due to ocean flooding. And, with ongoing climate change, the life-enabling monsoons are increasingly unpredictable.

Bangalore was not affected, but 2016 saw (for the first time as I recall) the necessity for massive water trains (the Jaldoot) to provide essential relief for drought-stricken areas. Between mid April and late July, some one hundred trains (each hauling up to twenty-four tank cars) carried 240 million litres of pumped (and later treated) river water the 343 kilometres from the Miraj region of Osmanabad to Latur and the Marathwada region of Maharashtra. Then the situation reversed in August/September 2017, with the worst monsoon-related floods in decades affecting more than forty-five million people across India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan. At least 1200 died. According to the International Centre for Climate Change and Development, this was at least partly a consequence of global warming.

Back in 2012, our Bangalore invitation came from Adam Smith at Nobel Media, as part of a joint initiative with the Swedish pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca to ‘increase understanding of the Nobel Prize awarded achievements within the fields of Physiology or Medicine among the general public, and to explain the benefits of these discoveries’. Accepting was easy. If used judiciously, the Nobel status provides some small opportunity to speak out. But how much of this is just noise in a vacuum? Working with real professionals, might I gain some better insights into how to communicate the importance of both science and a respect for evidence-based reality to those who seem to be disengaged, or even hostile, in the broader community? Ensuring that podcasts and the like are available in the long term clearly helps a lot with disseminating a measureable (by ‘hits’) message, but it’s still hard to know whether this is just preaching to the converted.

I was also curious about this city that presents as the nation’s innovation capital. Earlier trips had introduced me to impressive Indian entrepreneurs in therapeutics (Ranbaxy Laboratories, a pharmaceuticals company in New Delhi) and satellites (in Hyderabad), but what was the essence of Bangalore? The mandate was for me to give two formal (but fairly general) lectures and speak to established scientists and research students, first at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) and then at AstraZeneca’s substantial, long-established research and development facility. Both experiences offered a good chance to gain some clearer insights into the nature of India’s great industrial expansion. And so it proved to be!

Pioneering industrialist Jamsetji N Tata (1839–1904) conceived (and endowed prior to his demise) the IISc, known as India’s biggest and leading science institute. Founded in 1909 and accorded university status in 1956, the IISc listed recently in the top one hundred for the Times Higher Education Supplement World Rankings for Science and Technology, and as number twenty in the 2015 Global Employability university rankings. Visiting for a day gave me the sense that a well-recommended IISc PhD graduate would be a real asset for any laboratory. Apart from being trained by experienced mentors working in a quality setting, young Indian scientists have the great advantage (shared by Australians) that English (the primary language of science) is taught from an early age.

With a tall, central tower and fronted by a statue of JN Tata, the imposing colonial structure of the original institute anchors an extensive complex of modern, dedicated research buildings. Overall, with a lot of young people in evidence, the green and extensive campus certainly has the feel of a substantial university. The founding Director was English chemist Morris Travers, and the eminent CV Raman (1888–1970) was the first local Director (1933–48). Raman, who spent his whole career in India, was recognised by the 1930 Nobel physics prize ‘for his work on the scattering of light and for the discovery of the effect named after him’. The first Asian (and indeed non Caucasian) to be honoured by a science Nobel, Raman (laser) spectroscopy remains a key technology for molecular identification.

To put the IISc and the history of Indian science in some perspective, Australia’s CSIR (the precursor of the CSIRO) was not founded until 1926 and it was 1946 before an act of parliament established the Australian National University as a PhD-granting research institution. Then the first Australian Nobel Prize for work done in Australia was in 1960, to Sir Macfarlane Burnet. Thinking about that comparison makes it even more inappropriate that the deeply racist and ultimately unproductive character of the British Empire was sustained for so long. The entrenched discrimination against Indian officers in the British Army of India, for example, led many to become convinced nationalists, some of whom, after the fall of Singapore in 1942, fought alongside the Japanese in the Indian National Army.

Our formal day began with a morning welcome to the IISc by the head of the Department of Biological Sciences, Professor Dipankar Nandi, followed by a short tour and talks with staff and students, including podcast interviews by two students. Prior to my 5 pm lecture, there were lots of broad-ranging questions at a press conference with twenty-five print and broadcast media journalists. The exhausting, but interesting, day then ended at a relaxed dinner with faculty members at the IISc Guest House. Well (though not opulently) equipped, the IISc isn’t the country’s main biomedical research centre, but there was some work going on in areas of interest to me and, as always, it’s intriguing to hear incisive accounts of very different areas of science.

While the government of India is now a major supporter, the Tata family continues to take a strong interest in the IISc (it has been known locally as the Tata Institute) and, for me, a most memorable experience was chatting over lunch w

ith Rattan Tata, the CEO of Tata Industries. An immensely influential figure in India, he seemed totally committed to building the industrial strength and general wellbeing of his country. Perhaps with the Australian situation in mind, he was also vehement concerning his determination to ensure the continuance of India’s current media diversity. From what I encountered, the country does indeed maintain a highly critical, varied and open print media landscape.

The next day was spent at the AstraZeneca site. The company has a significant presence in some one hundred countries worldwide and the morning opened with a discussion of both the international operation and the scope of the Bangalore laboratories. I’ve visited and occasionally served on review committees for Big Pharma, but this was the first time I’d been given such a comprehensive overview of a major player in this highly globalised industry. Involved heavily in drug development, a particular focus of the Bangalore effort is to find new therapeutics for the treatment of tuberculosis. Multi, even total, drug-resistant tuberculosis is an enormous problem in the poorer countries, especially in those areas where AIDS is at high prevalence.

The quality of the AstraZeneca R&D effort in Bangalore seemed high, and the laboratories were much more opulently equipped than those I’d seen at the IISc. Clearly, no expense was being spared though, with contractions in the company at that time, a few I spoke with in this much less costly (in terms of salaries) Indian operation seemed concerned about their future job security. Again, it was a very busy day with interesting visits to, and presentations from, a spectrum of different groups. The lecture I gave on influenza immunity was to a much smaller and less diverse audience than that encountered at the IISc, and the day ended with a big party for the Bangalore AstraZeneca community, including a cultural entertainment featuring local dance and music.

Our main touristy experience for this short trip was a visit to the ornate Bangalore Palace. Extended greatly in the theme of Windsor Castle from an earlier residence, it was the home of the Rajah of Mysore, Krishnaraja Wodeyar IV (1884–1940) who, among many other contributions to improving the lot of the poor and developing the local educational landscape, donated some 150 hectares (plus additional funds) that enabled the establishment of the IISc and the realisation of JN Tata’s vision. Immensely wealthy, a gifted musician and the twenty-fourth ruler in the Islamic Wodeyar dynasty that governed Mysore from 1339–1940, Krishna IV was highly regarded by revered activist Mahatma Ghandi and has been described as the ideal of Plato’s Philosopher King. His enlightened Mysore administration was evidently a model for local government in India, and no doubt contributed greatly to the early industrial development of Bangalore.

Reflecting the mix of Indo/Saracen and British Imperial influence, the Palace is a truly extraordinary pile, with imposing staircases, grand ballrooms and English hunting and horse racing prints adorning the walls. But then there are minaret domes, massive carved doors, marble courtyards and screened upper galleries where the ladies of the house could observe, but not be observed by, the gentlemen moving below. Elephant themes are prominent, including a somewhat disconcerting encounter with giant elephant feet. Culturally, it is confusing and complex and, in that sense, a metaphor for modern India!

Dynasties come and go. The British Imperial Raj that prevailed when the Sultans of Mysore ruled and the IISc was founded is gone, as are the Princely States of India, though some of the families (including the Wodeyars) are still very wealthy. Rajah IV and JN Tata have left an enduring legacy of high-quality research and training. Apart from the IISc, which, among other areas, is prominent in fields from biochemistry to aerospace engineering, strengths at New Delhi’s All India Institute of Medical Sciences, the Chennai Institute of Mathematical Sciences, the National Institute for Solar Energy, the Space Research Program all point to a bright future for Indian science and high-tech industrial development

I grew up in a time when, while the Indian subcontinent had been freed (though with great suffering as a consequence of the India/Pakistan partition), elements of the old British Empire and influence were still very evident in African and other colonies. Most Australians were resolute anglophiles and, until 1947, we still carried British passports. English cars predominated until, in 1948, General Motors produced the locally made Holden. The upper middle-class aspiration for those emotionally embedded in the idea of British exceptionalism was to own a ‘Jag’. But, apart from the Mini-Cooper (which survives as a BMW brand) and the e-type Jaguar sports car, perhaps the most evocative English vehicle of the 1950s and 1960s was that rural workhorse, the Land Rover, particularly when dressed in military garb.

Tough and easy to maintain, the Land Rover nonetheless had a problem with breaking half-shafts in rough terrain and, in time, was substantially displaced by the even more robust Toyota Land Cruiser. The great irony is, of course, that badge names like Morris, Austin, Hillman, Standard and so forth have been replaced by Mazda, Honda, Toyota and Hyundai. And, in a reversal of the colonialist roles, the Land Rover/Jaguar Company is now a subsidiary of the Motors Division of Tata Industries. The world has changed, and it will not go back to what it was.

CHAPTER 15

Meeting of the rivers

IF AUSTRALIANS OF MY antique generation grappled with learning a language other than English, it was generally Latin (which is dead) and/or French (which is very much alive). French was the language of diplomacy and our British cousins, from whom we took many of our educational cues (some high schools still prepared for the Cambridge entrance examinations), could easily pop across the Channel to exercise their linguistic skills. Comme pour moi (or is it Quant a moi?), I learned French from an expatriate Scot and met my first native French speaker when I was in my twenties. But because we also became acquainted with the history and culture of France and (in combination with Latin) developed a better understanding of grammar, those four years of French were among the best experiences of my high school years. Like reading novels by smart people, learning French was an escape from boring! And we francophone postulants all learned to sing ‘Sur le pont d’Avignon / On y danse, on y danse / Sur le pont d’Avignon / On y danse tous en rond’.

In the late 1960s on a first camping holiday in Europe, we at last viewed the four remaining arches of the Pont d’Avignon-sur-Rhône celebrated dancing bridge. Calmed by twentieth century engineers, the Rhône rises in the Swiss Alps and, flowing south from Lake Geneva, is less liable to break bridges. And we also visited the massive Papal Palace that, through the fourteenth century, was home to a succession of five popes and two anti-popes (a job description to conjure with). Avignon’s Palais des Papes is a UNESCO World Heritage site, but any Rhône-side involvement I’ve had with palaces and UNESCO was 200 kilometres upriver at another (and more contemporary) palais, the Palais des Congrès de Lyon, the venue for the regular meetings of BioVision, the French-sponsored World Life Sciences Forum.

Much bigger than Avignon, Lyon sits at the junction of the Rhône and its largest tributary, the Saône, flowing south from the Vosges Mountains is genuine ‘eau de France’. Operating from 1988 and extended till its completion in 2006, the Palais des Congrès aligns along the left bank of the Rhône. Unlike the legendary Paris Left Bank of the Seine, though, the context is more business than bohemian. Lyon is historically a commercial centre, with big banks like the Crédit Lyonnais (now part of Crédit Agricole) and, from the late nineteenth century, a major vaccine and pharmaceutical industry built by the Mérieux family. And it’s also regarded (at least by the locals) as the gastronomic capital of France.

My first visit to Lyon in the late 1970s preceded the development of the modern congress centre. Working at the Wistar Institute (WI) in Philadelphia, several of us, including the Director, medical virologist Hilary Koprowski (1916–2013), flew the Atlantic to meet with some of the Mérieux people. Having made the first tissue culture grown (in WI-38 cells) rabies vaccine that was then developed commercially and sold by Mérieux, Koprowski was a close friend of Charles Mérieux (1907–2001), the the

n head of the Institut Mérieux (founded 1897). The WI-38 product was an important advance as the earlier, Pasteurian vaccines (made from ground-up, rabies virus-infected (then inactivated) rabbit brain or duck embryos) could cause the inflammatory brain disease allergic encephalomyelitis. Containing no brain tissue, the WI-38-grown product avoided this highly undesirable side effect. The Wistar vaccine is still sold as Imovax by Sanofi Pasteur, the inheritor of the Mérieux product line.

The Mérieux dynasty dates back to Marcel Mérieux (1870–1937), who started out as an assistant to France’s great hero of microbiology, Louis Pasteur. Reflecting the massive amalgamations that have transformed Big Pharma, the Institut Biologique Mérieux, which was founded in 1897 to produce vaccines and curative antisera (like anti-tetanus toxin, made by immunising horses), no longer exists as an independent drug company. The name Mérieux survives in the Foundation Mérieux, which focuses on ameliorating the toll of disease in developing countries; the French-based diagnostics company bioMérieux; and in Merial, Boehringer Ingelheim’s Animal Health (veterinary) division, which still has its headquarters in Lyon.

In the 1970s, the Mérieux scientists I met seemed to have been with the company a long time and, relaxed and comfortable in a somewhat benign environment, had no idea of the shape-shifting Big Pharma turmoil that was to come. I talked mostly with the head of their virology division, Monsieur Mountain, and met both Charles Mérieux and his son Alain, both of whom seemed pragmatic, sophisticated, thoughtful and decent human beings. The gastronomic high point of the visit was dinner at the restaurant of Lyon super-chef Paul Bocuse, with the culinary pièce de résistance being a chicken (stuffed with pâté de foie gras and truffles) cooked in a pig’s bladder. Perhaps because I was pretty low on the pecking order in such illustrious company, what landed on my plate was a rather scrawny chicken leg and, being both a culinary barbarian and rather hungry, I failed to detect the subtle flavours.

The Incidental Tourist

The Incidental Tourist